It is no longer a question that women have unique health needs, concerns and challenges. Among them are reproductive health, pregnancy and childbirth, sexual and intimate partner violence, and cancers that disproportionately affect women, including cervical and breast cancer. Women often face environmental and occupational health exposures both in the home and in the workplace that heighten health risks.

Migrant women face significant disparities with an additional layer of complexity and require different intervention strategies. The effects of language and cultural differences, lack of access to transportation and other barriers will be addressed in each section.

MCN has compiled resources that address these challenges and barriers to care with tools, education and programming for clinicians and migrant women. Many of our resources are available in the Resources sidebar. Please explore the following topics by clicking on each heading to learn more:

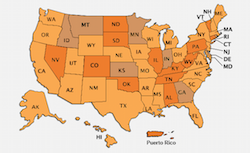

Migrant Women and Reproductive Health Issues Pregnancy The physical demands and environmental and occupational exposures related to work deserve special consideration in caring for pregnant migrant women in agriculture, service industries, and other employment sectors. Their risk status can be further complicated by ethnic and/or racial minority status, limited English proficiency, cultural beliefs related to gender and health care practices, and lack of access to health care services and lack of access to health care services. (See this map for a summary of prenatal coverage for unauthorized women by state.)

MCN is interested in assisting clinicians in their efforts to address the unique needs of pregnant migrant women. The prenatal branch of the MCN Health Network provides services to health centers and mobile women to improve continuity of care and records transfer. Additionally, MCN is involved in educating clinicians through continuing education presentations, patient information materials, articles and website resources, which are linked in the Resources sidebar.

Family Planning & Contraception Just as migration can disrupt continuity of care for chronic conditions, it can also disrupt access to family planning services and contraception. In the case of Latina migrants in the US, barriers to contraception may be larger than those in migrants’ home countries, where birth control like oral contraceptive pills and contraceptive injections are often available over the counter. Health care, though limited in those countries, is typically inexpensive; even discounted fees from a community health center in the US may be prohibitive. Consequently, many migrant women are lacking the family planning resources on which they had previously relied.

Breast & Cervical Cancer The barriers that prevent migrant women from getting cancer screenings are similar to those found in general health care services; language, transportation, lack of or insufficient insurance, and cultural norms prevent women from getting screened regularly. Additional hurdles include lack of knowledge about breast and cervical cancer; embarrassment, fear, and discomfort; lack of a regular health care provider; and the inability to provide test results when patients are on the move. For Latina migrants, the statistics are startling: Latinas in the US have a higher incidence of being diagnosed for cancer in later stages, making treatment more difficult. Uninsured Latinas with breast cancer in the US are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed at a later stage, resulting in lower survival rates. The rates of testing for Latinas are lower than that of white or African-American women, especially among recent Latina immigrants. These barriers result in significant disparities in the diagnosis of cancer, onset of treatment, and survival rates.

Sexually Transmitted Infections There is a need for culturally appropriate education related to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for immigrant women. The understanding of symptoms (or the lack thereof), transmissibility, prevention and treatment of STIs may be laced with myths and traditional practices. Treatments obtained from non-medical sources can result in consequences that range from uncomfortable to dire, depending on the severity of the infection.

Pap screening may offer a less threatening opportunity to provide education about STIs, given the link between HPV infection and cervical cancer. Discussion of concepts such as the risk of multiple sexual partners, the use of condoms, and the importance of screening apply to all STIs.

In addition to education, healthcare workers need to include questions in women’s health history-taking related to STI symptoms, past infections and treatments.

Educational materials related to STIs are listed in our Tool Box here . Information about HIV/AIDS care is available here .

Menopause Coming Soon!

Migrant Women and Environmental & Occupational Health Issues Pesticide Exposure Migrant farmworker women experience unique risks related to the physical demands and environmental exposures related to their work. Health risks to migrant women associated with exposure to pesticides has always been a concern of clinicians working with farmworkers. This concern was heightened by birth defects which occurred in babies born in 2005 to four women who worked as farmworkers at the same farms in both North Carolina and Florida. The investigation of these cases by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services concluded that “there is evidence…that the women’s work environment likely put them at an increased risk of overexposure to pesticides”, and their recommendations included an initiative “to strengthen efforts to educate farmworkers about their rights under the Worker Protection Standard, to develop pesticide education materials targeting women of childbearing age.”

In addition to direct pesticide exposure, migrant women experience other occupational and environmental risks associated with their working and living conditions. Occupational risk can also be transferred to women from family members through secondhand exposure to chemicals and through location of housing close to agricultural fields.¹

It is essential that clinicians and others serving migrant and farmworker populations have access to research, training and culturally appropriate tools that can help them provide adequate care to their patients. See the Resources sidebar for relevant resources and links below to a few of MCN’s many resources for clinicians on environmental health:

References:

Arcury, T.A., Quandt, S.A., Rao, P., Doran, A.M., Snively, B.M., Barr, D.B., Hoppin, J.A. and Davis, S.W. (2005). Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure in Farmworker Family Members in Western North Carolina and Virginia: Case Comparisons. Human Organization. 64(1). Arcury, T.A. and Quandt, S.A. (2003). Pesticides at work and at home: exposure of migrant farmworkers. Lancet, 362: 2021. Other Risks Exposure to lead and other chemicals pose threats to general and reproductive health, as do a wide range of other factors such as heat exposure, musculoskeletal disorders, dermatological problems, etc.

Exposures to lead can occur in a variety of ways; lead contamination has been found in recent years in medications manufactured outside of the US, imported toys and candy, paint chips from older housing, and even in chapulines, or grasshoppers, from parts of Mexico, which are consumed as a snack.

Risk status can be complicated further by ethnic and/or racial minority status, limited English proficiency, lack of access to health care services and cultural beliefs related to gender and healthcare practices. Learn more about lead and other environmental risks here:

Migrant Women and Violence Sexual & Intimate Partner Violence Sexual and intimate partner violence (S/IPV) is a widespread problem in the immigrant and migrant community. Women in these populations are at a substantial disadvantage and are significantly more vulnerable to these types of violence. Language barriers, economic hardship, and isolation from their communities, support networks, and cultures of origin make it increasingly difficult to come forward and report these abuses. Women often suffer in silence for fear of losing their jobs or enduring legal ramifications like being reported to immigration. In addition, immigrant and migrant women have less access to social and medical services increasing their negative health outcomes. Intimate partner violence is an especially sensitive situation, with the perpetrator of violence being a loved one, usually a former or current partner or spouse.

MCN has worked to prevent S/IPV for many years. Our Family Violence Prevention program includes a number of projects, including the innovative Hombres Unidos Contra La Violencia Familiar , which seeks to address S/IPV by engaging Latino migrant men to become advocates against S/IPV.

We encourage all clinicians to screen female patients for S/IPV. Click here for a low-literacy screening form example.

Sexual harassment A 2012 report by Human Rights Watch entitled Cultivating Fear

Trafficking Trafficking amounts to modern-day slavery. Thousands of individuals are trafficked into the US every year, and the vast majority of them are women. Trafficking victims are coerced into working. In the case of sex trafficking, women are forced into prostitution or the sex entertainment industry. But trafficking is not limited to the sex industry. Trafficked victims may be coerced into working in industries such as agriculture, sweatshop factory work, and domestic, janitorial, or restaurant work. Clinicians must be aware of the possibility that patients may be the victim of trafficking. During migration, women are especially vulnerable to trafficking. Click the Resources sidebar for additional resources, including Look Beneath the Surface , a program of the Office for Children and Families .

Case Study: Anna* had been trafficked into the sex trade in Florida at the age of 11, and was pregnant by age 13. After having her baby, she migrated to North Carolina. In North Carolina, her baby began to be sick; he had skin issues as a result of Anna’s chlamydia. The presence of an STI and a pregnancy at such a young age are both indicators of trafficking, but Anna’s case was not exposed as an incidence of trafficking, until her local health clinic spent time cultivating the relationship with Anna and providing a safe place for conversation. It took about a year for the health clinic to determine that she was the victim of trafficking.

What You Can Do for Migrant Women What You Can Do We can lessen health disparities and strengthen access to care for migrant women through advocacy and clinical systems change.

Raise your voice. Clinicians are at the front lines of care. We are the most effective advocates for change within the clinician community and as a bridge between health providers and your communities.

You can be an advocate internally, changing clinical systems from within, and externally, a voice for change in your community or larger health arena. Community health workers are vital allies in this effort, both lay health educators and clinical health workers who are liaisons between a clinic and the community.

Internal Advocacy Internal Advocacy promotes clinical systems change from within.

Examples of Clinical Systems Change include:

Allow walk-in appointments; Extend care hours beyond the workday; Offer group visits; Incorporate promotores de salud and other community health workers into the clinical care team; Ensure culturally competent care in the primary languages understood by the migrant communities; Provide vouchers for transportation to clinics and specialty appointments; Provide access to child care; Make sure education materials are culturally appropriate and available in the languages spoken by members your community; Rely on resources like promotores, videos, fotonovelas, and picture-based comic books rather than literature-based education to address issues as diverse as reproductive health, pregnancy and childbirth, sexual and intimate partner violence, cervical and breast cancer, and pesticide exposure; Enroll migrant women in Health Network . MCN’s Health Network provides care coordination to ensure women receive the care they need, whether for prenatal care or for care for specific diseases or chronic conditions. External Advocacy External Advocacy strengthens health care through outreach to the community. Clinicians can advocate for policy changes at local, regional, state and federal levels.

Examples of external advocacy include:

Write letters to the editor supporting legislation to protect battered women Join sign-on letters focused on migrant women and specific women’s health issues from your professional organizations to government agencies e.g. the Department of Justice, to the EPA, to the Department of Health and Human Services), and to your Congressional Representatives. MCN searches for opportunities to add our voice to others. Join community campaigns, locally, statewide, regionally and nationally, to raise awareness of family violence, pesticide exposure, and lack of access to prenatal care. Resources Emerging Infectious Diseases: Zika Virus RNA Replication and Persistence in Brain and Placental Tissue

Contact: Candace Kugel , MS, CRNP, CNMckugel@migrantclinician.org