- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Mon, 02/02/2015 | by Amy Liebman

Editor's note: This post, written by MCN's Amy Liebman, first appeared in The Pump Handle, a public health blog. Please visit The Pump Handle at http://scienceblogs.com/thepumphandle/.

Pesticide drift from a pear orchard sickened 20 farmworkers laboring in a neighboring cherry orchard in April 2014, in Washington State, according to a new Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interestingly, and critically, the exposure came to light because a newspaper reporter tipped off the Washington Department of Agriculture, who then contacted the Washington Department of Health. Where were the clinician reports?

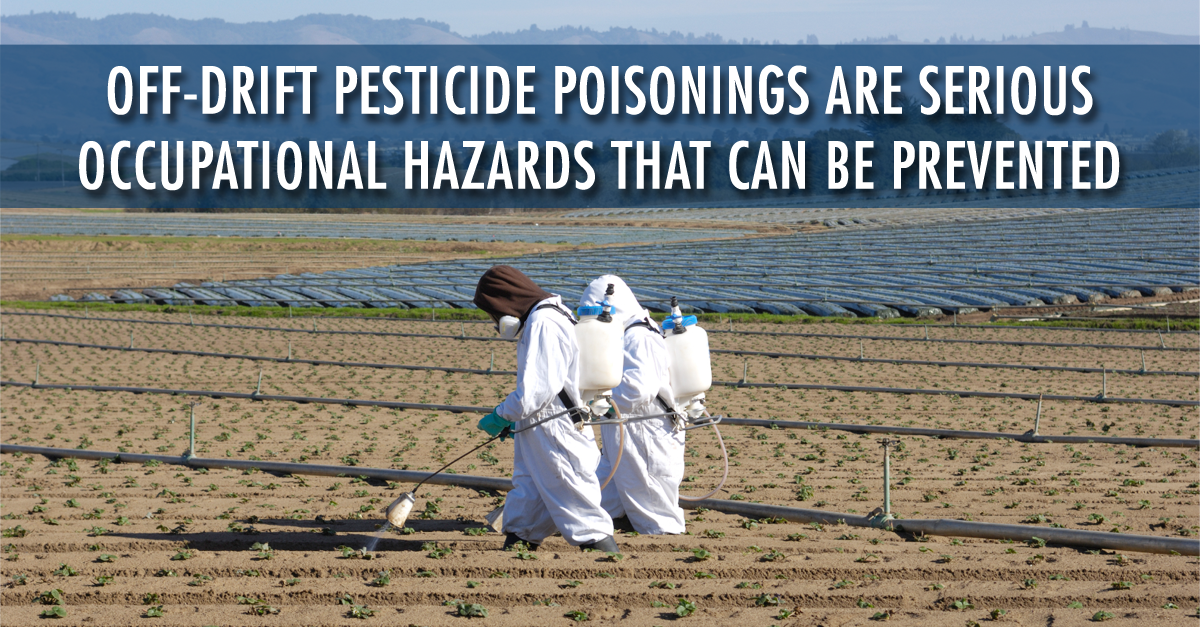

Off-drift pesticide poisonings are serious occupational hazards that can be prevented; this instance was no exception. Two workers in full personal protective equipment including respirators applied three newly marketed pesticides to an orchard. Farmworkers in an adjacent farm, unaware of the scheduled spraying, began feeling ill within minutes of being exposed to the pesticide drift. Their crew leader called 911, and medical personnel provided emergency care on-site. Sixteen of those 20 sought additional medical care after receiving emergency care, with symptoms including headache, nausea, eye irritation, and respiratory issues. Two weeks later, authorities followed up with eight of the workers. Six of them were still exhibiting symptoms from the exposure.

While it is prohibited to apply agricultural pesticides when it can result in the exposure of people, no regulation requires farmers to notify neighboring farms of upcoming pesticide applications. California is the only state that recommends workers be notified of area pesticide applications. This case highlights why such notification is needed. It also underscores the importance of surveillance. When cases like this come to light, regulatory agencies can take appropriate action to strengthen policies. That is why it is a law in many states, including Washington, for clinicians to report pesticide exposures. These reports allow agencies like each state’s health department, the CDC, and the Environmental Protection Agency to follow trends, and to identify– and potentially remove — pesticides or practices that are repeatedly found to be hazardous. In this case, multiple clinicians likely treated the 16 workers who sought care, but none of them filled out a report.

Farmworkers do not always have a reporter inquiring about about pesticide poisonings. It is more likely there will be a clinician caring for a poisoned worker. That clinician can make all the difference for the overexposed worker — and other farmworkers– by reporting it. Clinicians have a critical role in preventing tomorrow’s pesticide poisonings by ensuring that today’s are accurately reported.

Amy K. Liebman, MPA, MA, is the Director of Environmental and Occupational Health at Migrant Clinicians Network, a nonprofit dedicated to health justice for the mobile poor, creating practical solutions at the intersection of poverty, migration, and health.

Pesticide drift from a pear orchard sickened 20 farmworkers laboring in a neighboring cherry orchard in April 2014, in Washington State, according to a new Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interestingly, and critically, the exposure came to light because a newspaper reporter tipped off the Washington Department of Agriculture, who then contacted the Washington Department of Health. Where were the clinician reports?

Off-drift pesticide poisonings are serious occupational hazards that can be prevented; this instance was no exception. Two workers in full personal protective equipment including respirators applied three newly marketed pesticides to an orchard. Farmworkers in an adjacent farm, unaware of the scheduled spraying, began feeling ill within minutes of being exposed to the pesticide drift. Their crew leader called 911, and medical personnel provided emergency care on-site. Sixteen of those 20 sought additional medical care after receiving emergency care, with symptoms including headache, nausea, eye irritation, and respiratory issues. Two weeks later, authorities followed up with eight of the workers. Six of them were still exhibiting symptoms from the exposure.

Off-drift pesticide poisonings are serious occupational hazards that can be prevented; this instance was no exception. Two workers in full personal protective equipment including respirators applied three newly marketed pesticides to an orchard. Farmworkers in an adjacent farm, unaware of the scheduled spraying, began feeling ill within minutes of being exposed to the pesticide drift. Their crew leader called 911, and medical personnel provided emergency care on-site. Sixteen of those 20 sought additional medical care after receiving emergency care, with symptoms including headache, nausea, eye irritation, and respiratory issues. Two weeks later, authorities followed up with eight of the workers. Six of them were still exhibiting symptoms from the exposure.

While it is prohibited to apply agricultural pesticides when it can result in the exposure of people, no regulation requires farmers to notify neighboring farms of upcoming pesticide applications. California is the only state that recommends workers be notified of area pesticide applications. This case highlights why such notification is needed. It also underscores the importance of surveillance. When cases like this come to light, regulatory agencies can take appropriate action to strengthen policies. That is why it is a law in many states, including Washington, for clinicians to report pesticide exposures. These reports allow agencies like each state’s health department, the CDC, and the Environmental Protection Agency to follow trends, and to identify– and potentially remove — pesticides or practices that are repeatedly found to be hazardous. In this case, multiple clinicians likely treated the 16 workers who sought care, but none of them filled out a report.

Farmworkers do not always have a reporter inquiring about about pesticide poisonings. It is more likely there will be a clinician caring for a poisoned worker. That clinician can make all the difference for the overexposed worker — and other farmworkers– by reporting it. Clinicians have a critical role in preventing tomorrow’s pesticide poisonings by ensuring that today’s are accurately reported.

Amy K. Liebman, MPA, MA, is the Director of Environmental and Occupational Health at Migrant Clinicians Network, a nonprofit dedicated to health justice for the mobile poor, creating practical solutions at the intersection of poverty, migration, and health.