- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Thu, 06/21/2018 | by Claire Hutkins Seda

Yesterday, President Trump signed an executive order that halts his administration’s policy of separating children from their immigrant parents while crossing the border. Since the start of Trump’s “zero-tolerance” policy, all border crossers who seek to claim asylum have been arrested and criminally prosecuted. Since the 1997 Flores settlement, and more specifically under the 2015 amendment of the settlement, federal policy has assured that children -- including those held in detention with their families -- should not be held in detention for longer than 20 days. Trump has directed Jeff Sessions, the Attorney General, to file a request to modify Flores so that children can be held in detention, with their families, until their parents’ criminal and immigration proceedings are concluded -- which could potentially mean that children may live months, or possibly years of their childhood in federal detention. This potential expansion of family detention is troubling.

Detention is an inappropriate setting for a child.

We have seen children in long-term detention before. In 2014, at the height of the “border surge,” thousands of children were held in detention with their mothers after trying to claim asylum at the border. A full year later, many of the families still languished in detention. At that time, we approached Dr. Luis Zayas, who had visited two of the facilities and interviewed a number of detainees, to better understand the health needs of children in detention. Here’s what he said:

“We know that detention is unnatural. What we’re doing is we’re devastating the kids’ lives, and their mothers. There is deprivation of freedom; these kids are not experiencing a normal childhood. They can’t get on a bike and go to the corner store and get something and hang out with the kids. They’re constantly being watched. There are guards who are not very friendly. We’re learning more about the neurobiology of stress and trauma -- and how it affects people lifelong. We’ve got to be prepared to work with these kids now, while they’re inside -- but also as soon as they come out.

We’ve got three levels of trauma, as I said: there’s pre-migration, peri-migration, and then there’s post-migration -- the detention. We’re going to have to work as clinicians at those three levels. And I think we may have to work backwards, because I think the most recent trauma will be what they experienced [in the immigration centers]. We need to be aware of that.

In those conditions -- sure, they have showers, clothes, and beds -- but there was a constant vigilance that these kids had to maintain, and the stress levels were high.”

“We know that detention is unnatural. What we’re doing is we’re devastating the kids’ lives, and their mothers. There is deprivation of freedom; these kids are not experiencing a normal childhood. They can’t get on a bike and go to the corner store and get something and hang out with the kids. They’re constantly being watched. There are guards who are not very friendly. We’re learning more about the neurobiology of stress and trauma -- and how it affects people lifelong. We’ve got to be prepared to work with these kids now, while they’re inside -- but also as soon as they come out.

We’ve got three levels of trauma, as I said: there’s pre-migration, peri-migration, and then there’s post-migration -- the detention. We’re going to have to work as clinicians at those three levels. And I think we may have to work backwards, because I think the most recent trauma will be what they experienced [in the immigration centers]. We need to be aware of that.

In those conditions -- sure, they have showers, clothes, and beds -- but there was a constant vigilance that these kids had to maintain, and the stress levels were high.”

Dr. Zayas specified that 14 days was a long period of time for detention, but necessary for processing and resettlement of asylum seekers. The new policy threatens to hold them for much longer, further stressing the health of the children. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have profound and life-long health effects. On top of the trauma of a violent home, and the danger and fear during a long migration, we are now perpetuating a third layer of trauma: the trauma of detention. Read more about the health implications of ACEs here and here.

An increase in family detention may strain an already inadequate health care system at detention facilities.

The long-term health of the children isn’t the only health concern in detention. A new Human Rights Watch report uncovered “subpar and dangerous practices” that constitute “systemic deficits in immigration detention facility health care.” Over a 29-month period, 15 detained immigrant deaths had been reported. The report concluded that 8 of the 15 public death reviews show that inadequate medical care contributed or led to the person’s death.

An increase in the number of families detained and in the duration of detention threatens to further strain a health system that is already underperforming. Increasing the capacity in current facilities, building and launching new facilities, and changing staff protocol may result in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, further increasing the health needs of the population.

Medical Review for Immigrants: Saving immigrants’ lives by getting them the care they need.

Unfortunately, many immigrants are left in detention with urgent health needs going unmet -- threatening their long-term health. For many, their conditions become more difficult and more costly to treat as time wears on. For some, the conditions are life threatening.

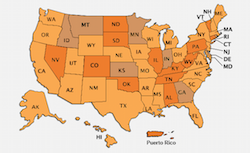

Migrant Clinicians Network is seeking to change that. Through Medical Review for Immigrants, a new initiative of MCN, a physician is mobilized to quickly provide a Letter of Declaration for an attorney to request humanitarian parole for a seriously ill immigrant client, which enables the client to be released to receive essential care. Once released, MRI then assures that the client reaches the treatment she needs, with records transfer, follow-up services, and case management. MRI leans on MCN’s clinical network of over 10,000 constituents and over 30 years of experience working with health care providers coast to coast, and utilizes MCN’s Health Network, a proven cost-effective bridge case management system for patients who are moving while needing ongoing care. Medical Review for Immigrants is just getting started -- but you can help us. Donate to MCN today to help us assure that immigrants with urgent and unmet health needs can get out of detention and into care. Learn more and donate here.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.