- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Wed, 05/23/2018 | by Monique Vasquez

[Editor’s Note:This post comes to us from Monique Vasquez, Health Network Intern and student at UT Austin Steve Hicks School of Social Work. You can read her previous blog post here.]

Two weeks ago, Donald Glover, under his music artist name Childish Gambino, released a haunting music video, “This is America.” As many have already pointed out, the video’s imagery is powerful. The riots, policing, and chaos in the background are easily ignored if viewers fail to see the whole picture and focus only on Childish Gambino, his dancing, and his smile.

When we hear about poor outcomes for people of color, it is often easier to focus on the individual, to label them as someone who has made “bad choices” and to assign blame when they encounter hardships or trauma. Once we ignore the background, we allow ourselves to ignore the larger, painful picture of racial discrimination present in our systems. Just as we should take in all the details of the video, we cannot dismiss the need to talk about race and racism, and we cannot look away from the whole picture.

Race and racism are difficult and uncomfortable conversations to have -- and it can be even more difficult to have these conversations in a professional setting. As an intern with Migrant Clinicians Network, I appreciated such conversations as I participated in an intense 2.5-day Undoing Racism training through the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond. The training was hosted by the City of Austin Equity Office, which was founded in 2016 to address racial and systemic inequity in Austin.

The training included a look at the ways in which organizations continue to marginalize or treat people of color differently because of structural racism. While the people working for the criminal justice system, education system, the non-profit system, and child protective service agencies may intend to provide helpful services and can produce good results, people of color are often harmed or are unable to benefit at the same rate as white populations. This is because the systems were created by people who were legally recognized as white, with the intention to benefit white people and exclude or harm non-white populations. When people of color fought for inclusion, these systems were not restructured to include or serve them, or to account for the lack of equal status after generations of harm and unequal treatment. As an example, although Brown v. Board of Education called for integration of schools, it didn’t account for ways to help populations who were previously receiving “separate but unequal” education due to low resources. Today, black and brown populations continue to be more likely to go to underfunded schools and to have lower graduation rates.

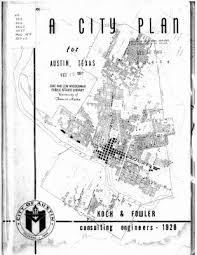

Increasingly, health providers are recognizing the large impact that zip code has on life expectancy and health-- often termed the “social determinants of health” -- and we can trace back how these social determinants arose because structural racism has affected where people live and what services they could get. Austin itself provides a clear example of how structural racism persists. The City of Austin’s Master Plan of 1928 created zoning ordinances which prevented African Americans and Mexican Americans from having access to city services and utilities outside of designated districts and caused our I-35 freeway to become a racial dividing line. Today, Austin is among the most economically segregated cities in the United States, and the only large fast-growing city with a declining African-American population. For generations, Austin neighborhoods with high concentrations of people of color have built their communities with fewer services and less resources than white neighborhoods including city services like public transportation, park services, sidewalks, public health resources for physical and mental health, and roads. Additional disparities are evident in healthy food access, employment opportunities, and school funding.

People of color face disparities in health: worse birth outcomes, higher rates of chronic disease, higher rates of uninsurance or underinsurance. As Austin expands, more and more people are moving to neighborhoods east of I-35 and in the south, and more services and resources are going to this area -- but the people who have lived in this area for generations are less likely to benefit as rising property taxes and the increasing cost of living are pushing them out.

While these disparities are noticeable here, Austin is not unique. The effects of structural racism persist in cities and rural areas across the United States.

One of the valuable lessons I learned from the training is that to make a difference we must love our systems enough to be critical consumers of them and push them to change for the better. Change does not often come from the status quo, but from people who organize to change the system. Change must draw from the voices of those who are most affected and these voices must be included in the changemaking process.

Migrant Clinicians Network is at the “intersection of poverty, migration, and health” and this includes an analysis of how racism is linked to these issues. The people served by MCN’s clinician constituency are met with challenges from multiple systems. If we want to care for these populations, we must be conscious of the way that racism still lives in these systems, we must work hard to recognize internalized racism, to call it out in our systems and we must fight to urgently dismantle racism and restructure our systems from an anti-racist lens.

Here are some of Monique’s recommendations for further reading:

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond

Mayor’s Task Force on Institutional Racism and Systemic Inequities

The New York Times Magazine’s recent article, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.”

The PBS multi-part, four-hour documentary on racial and socioeconomic disparities in health -- Monique recommends parts two and three.

For an Austin perspective, read “Austin Health Leaders Call Racism a Root Cause of Ill Health” from the Austin American-Statesman

Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology, 35(4), 407.

NPR’s article, “Racism Is Literally Bad For Your Health.”

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond

Mayor’s Task Force on Institutional Racism and Systemic Inequities

The New York Times Magazine’s recent article, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.”

The PBS multi-part, four-hour documentary on racial and socioeconomic disparities in health -- Monique recommends parts two and three.

For an Austin perspective, read “Austin Health Leaders Call Racism a Root Cause of Ill Health” from the Austin American-Statesman

Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology, 35(4), 407.

NPR’s article, “Racism Is Literally Bad For Your Health.”

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.