- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Tue, 09/04/2018 | by Alma Galván

The health center should:

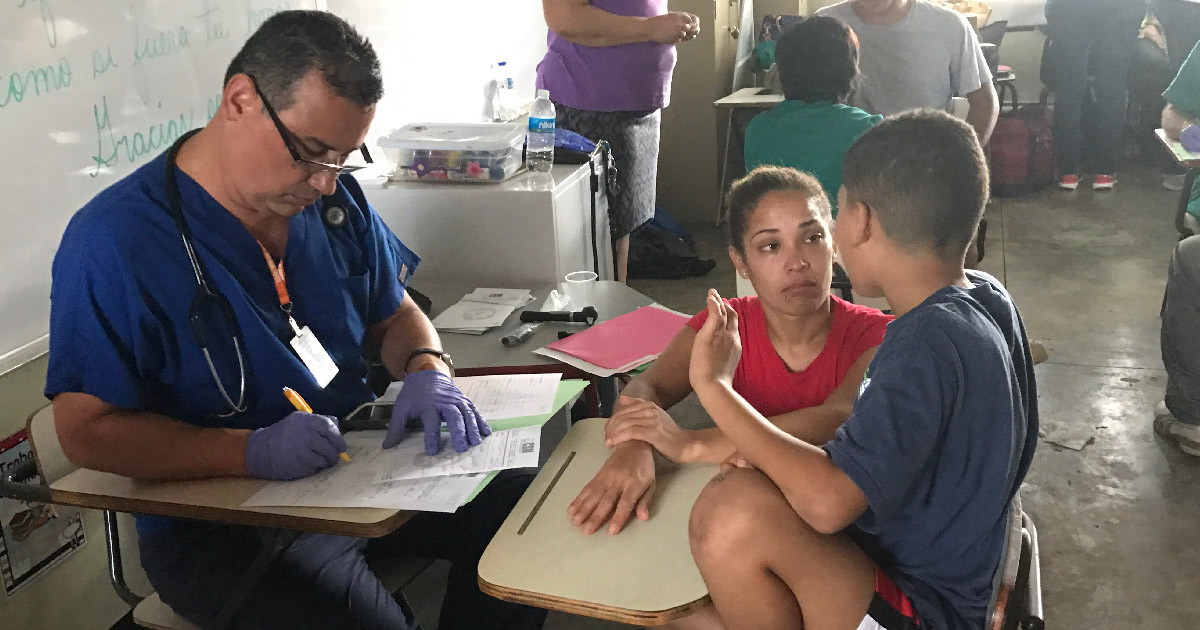

photo credit: CSM

[Editor’s Note: September is National Preparedness Month. We are once again deep into hurricane season. Health centers in hurricane-prone regions continue to update their preparation plans to assure readiness in the face of disaster. This interview is from the current issue of Streamline, Migrant Clinicians Network’s in-print quarterly clinical publication providing information and resources to frontline clinicians working with mobile underserved populations. Read the complete current issue and view back issues here. Want to subscribe? Send your mailing address to contedu@migrantclinician.org. This article has been edited for relevancy and brevity.]

By Alma Galvan

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico in what is called the strongest hurricane to ever hit the island. The devastation was widespread and long-lasting -- both to local infrastructure and to residents’ health. Almost one full year later, power outages occur less often, water systems are largely back online, and communities are beginning the long path to rebuilding. Within those rebounding communities, however, health centers are still struggling to work at capacity and, in particular, to address continued mental health concerns. In April, Lorena Torres, PhD, from Corporación de Servicios Médicos, a Community Health Center in Hatillo, Puerto Rico, joined several other leading experts for MCN’s on-the-ground workshop, “Learning from the Past and Looking to the Future: Natural Disasters and Our Patients.” Dr. Torres’ clinic serves patients from numerous vulnerable populations including agricultural workers, homeless patients, substance users, and single mothers. Earlier this year, Dr. Torres described her perspective on disaster preparation, clinician burnout after a disaster, and plans for the future.

Why is it important for clinicians to pay attention to vulnerable populations when working on disaster preparedness plans in regards to mental health?

The process of preparing for a disaster depends largely on how emotionally stable and how educated the person is. Vulnerable populations do not have access to a lot of resources, so the doctor plays a vital role in educating patients about proper health management and identifying patients who need specialized mental health services to assure they can receive adequate services and can weather the disaster.

What reactions do you remember from the first days after Maria, and what does it say about the mental health needs of your population?

After Hurricane Maria, reactions were of frustration, helplessness, and uncertainty. The reality was that we were not prepared for an event like this -- not individually, not governmentally and not organizationally. We must remember that what we are experiencing is the result of many factors. At that historic moment [when Hurricane Maria struck], Puerto Rico was already going through a bankruptcy that affected access to services and increased uncertainty. On top of that, we have a high level of high school dropouts, a high rate of chronic conditions, and one of the highest poverty levels in North America. What [has now] shifted on my island is this increase in a range of mental health conditions after the disaster, so our need for education and services is enormous -- and the work is titanic.

photo credit: CSM

What patients do you remember the most -- do you have one story to share?

After the hurricane, I remember listening to a patient whose access to his home was destroyed. He had to wade across a river every day to get to work and make that effort. Now, seven months after the hurricane, his situation remains the same. These types of situations continue.

What did your health center do to prepare for the increase in mental health concerns, and what would you do differently?

It actually wasn’t something that was thought through officially [beforehand]. The hurricane [touched down on a] Wednesday, and I anticipated that the worst cases would present to the clinic on Monday, and the clinic would receive patients as always, with perhaps some kind of disruption of electricity, but nothing more. The reality was otherwise. My home is well constructed and designed for hurricane-force winds. During the hurricane, when water started to leak through the doors and windows, and the winds blew my garage door off and threatened to destroy the entryway, I then understood that this was something much more powerful than we had thought and that our lives would be changed forever -- and they were. Immediately, after I assured the basic safety of my family and home, and after waiting in line for seven hours to get $20 of gasoline, I got to work and, with my colleagues, I began visiting shelters and our communities [directly].

[What the hurricane taught me was] you must train all personnel in handling the emotional [responses] of patients after a disaster and provide them with self-care strategies so that they can handle the situation.

How can clinicians really address the mental health needs of patients when they themselves have to deal with the disaster as well?

The importance of advanced planning. For example, as professionals, we have more economic resources to access goods and services. But even for us, after the hurricane, we could spend a full day to complete a task that normally took an hour. The health center, in this case, could develop flexible scheduling for the professional staff [so that we] have time during the week to take the necessary steps to keep our families safe and [homes] well stocked. This approach would provide peace of mind to health professionals, so they can better work with their patients.

photo credit: CSM

How do you address post-disaster burnout?

We need to talk about our thoughts and emotions, set agendas and take time for self-care activities, enjoy the people we love. Good nutrition and physical activity should also be a part of the process.

What part of your presentation do you think is the most critical?

Strategies to establish a relationship of support and protection of mental health response teams. [See text box, below.]

What is your next step -- what will you be doing in the clinic for the next six months?

My plan is to continue providing quality mental health services and to educate the population so that the experience of Hurricane Maria has not been in vain and we are better prepared for the next disaster.

Get more resources at the CDC’s National Preparedness Month webpage: https://www.cdc.gov/phpr/npm/npm2018.htm.

Caring for Mental Health Response Teams After a Disaster

Dr. Torres’ presentation on disasters and mental health included a number of best practices and lessons learned after Hurricane Maria. Here are her tips on how health centers can best serve their mental health response teams to assure their effectiveness and avoid burnout:

Caring for Mental Health Response Teams After a Disaster Dr. Torres’ presentation on disasters and mental health included a number of best practices and lessons learned after Hurricane Maria. Here are her tips on how health centers can best serve their mental health response teams to assure their effectiveness and avoid burnout:The health center should:

- Provide their mental health practitioners with as much information as possible about what has happened.

- Develop a system of support between the team members.

- Report regularly to team members about the status of their families and their location.

- Meet regularly with each clinical team to check in.

- Be given time and space to have regular telephone contact (when possible) with family and friends.

- Be given time off to protect their health.

- Conduct walks together away from the work area.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.#mce_temp_url#

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.