- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Wed, 09/18/2019 | by Claire Hutkins Seda

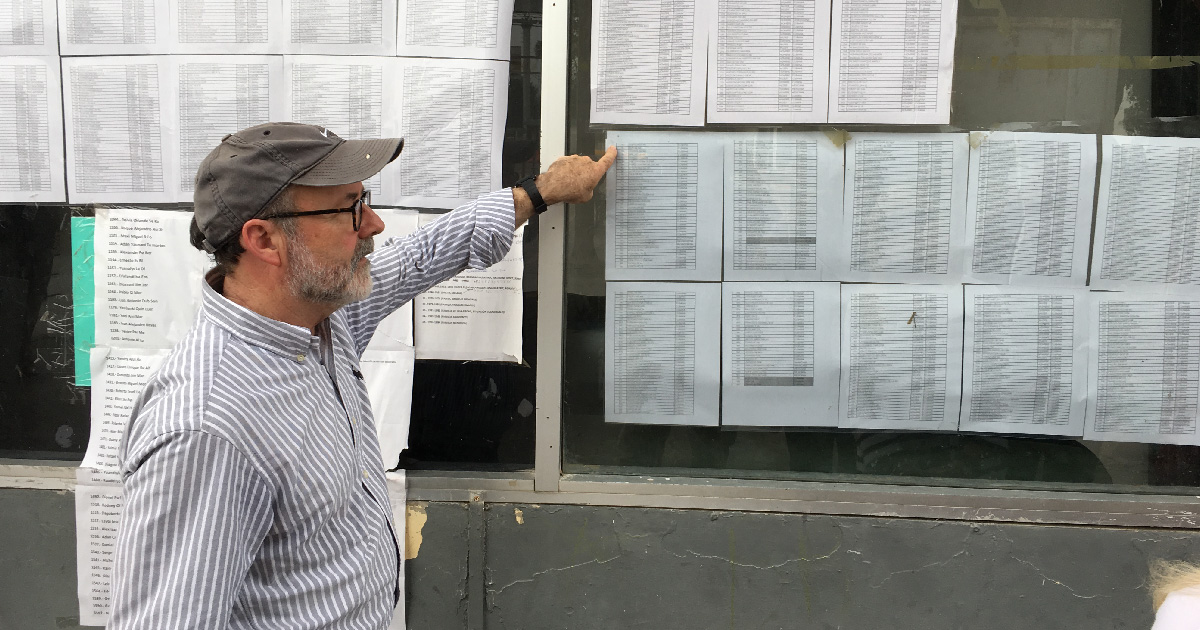

[Mike Seifert looks at list of names of immigrants waiting to cross the border.]

[Editor’s Note: It’s difficult to get a good sense of what’s happening on the border. That’s because it’s rapidly changing. Here, we get a rundown of the last two years in the Rio Grande Valley. Read more about the Migrant Protection Protocols and the Safe 3rd Country rule, which are both rapidly affecting the border region and the ability of asylum seekers to ask for asylum in the US, here.]

“The Rio Grande Valley, which is one end of our very long southern border, is an entity in and of itself,” summarized Mike Seifert, a border advocate and resident for over 30 years. The region’s isolation is assured by the US-Mexico border to the south and the border patrol checkpoints along the two highways leaving the region, roughly 75 miles north of the border. “We’re essentially stuck here,” he said. In the four counties of the Rio Grande Valley, there’s no public hospital, little industry, poorly resourced schools, and few social services. “There’s no real good reason to move here as an immigrant, if you are looking to create a better situation for your family,” Seifert explained. “On the other hand, the Rio Grande Valley is a part of a border region. People stay here because their families and friends are just across the way in Mexico.” The Rio Grande Valley, for this reason, is an immigrant community with more than 85 percent of the residents claiming a Mexican-American heritage.

For the tens of thousands of asylum seeking families and migrants who cross the border at the Rio Grande, either through the water or across the bridge, the region is simply a stopover on the way to family in another part of the country, giving the region a transitory atmosphere. Around 5,000 unaccompanied minors are housed in facilities run by the Office for Refugees and Resettlement. Up until this summer’s implementation of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), in which individuals applying for asylum must stay in Mexico, the families who crossed the border here were released in the area, and were eager to move on -- usually within a day -- to their next destination. Many in Seifert’s community have been providing short-term basic services to migrants after their release, from social services to health care, but in recent months, the situation in the Rio Grande region has become even more volatile, he says, as the federal government defines and redefines their enforcement activities. “That’s been an extraordinary challenge to figure out how to best help folks,” he admitted.

[Photo by Karl Hoffmann]

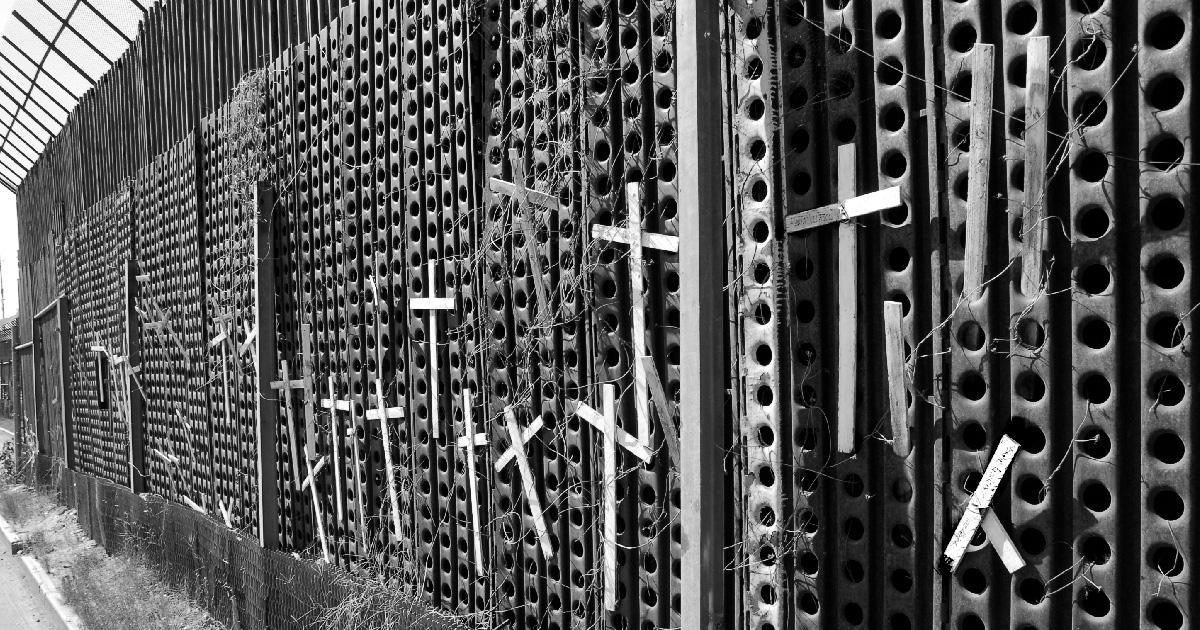

“The Border Wall is a Lighthouse”

As a border resident, Seifert has had an up-close view of the influx of migrants in the last two years, how they compare to earlier waves of migrants in decades past, and the response by border authorities that most of us only read about. Decades ago, the average border crosser was a Mexican male, searching for work in the United States. Each time such a migrant crossed, his prime aim would be to avoid detection by Border Patrol, work for several months, save some money, and return the same way, back to Mexico. Today’s Border Patrol infrastructure was formulated in the wake of 9/11, when border security was increased. Many of those who once traveled back and forth across the border simply settled in the US to avoid the higher risk of contact with enforcement.

Today’s average border crosser does not fit the profile for which the Border Patrol has been organized, Seifert says. “The border patrol is picking up people who are surrendering to them. They are family units, traumatized in unimaginable ways,” and mostly running away from violence and instability in the Northern Triangle, Seifert explains. Rather than being motivated by the ‘pull factors’ of better-paying work in the US, these families are fleeing from ‘push factors’ of harassment, abuse, extreme poverty, and death in their home communities, seeking safety with family members who are already living in the US.

Since 2014, many of these families and thousands of unaccompanied minors have crossed the border. Once they cross, they immediately seek out Border Patrol to surrender themselves and ask for asylum. The border wall in the Rio Grande Valley region is well inside the US-Mexico border line. Seifert recalls an anecdote retold to a congressional delegation about the border wall: “If we walk a half mile down that way, we’ll find 600 people sitting there,” a guide to the delegation said. Coyotes, who are hired to guide families to smuggle them into the US, bring migrants to the Rio Grande River, provide an innertube to cross, and instruct the families to walk toward the wall, the guide to the delegation said. “They tell them, ‘Walk a half mile til you get to the border wall and then just take a seat there,” as both sides of that stretch of the wall is in the US, Seifert recalled. “Eventually, Border Patrol will come along and pick you up. So, rather than being a deterrent, the border wall is a lighthouse.” This anecdote emphasizes how today’s migrants are not wishing to cross the border undetected; on the contrary, they are eagerly looking for Border Patrol.

Seifert says it’s worth noting that it is indeed their legal right as an asylum applicant to ask for admission to the US after crossing without authorization: “There is no illegal way for an asylum seeker to be in the US -- that’s the whole point” of seeking asylum, as people flee to the country, he asserted. Yet, many pundits question why migrants would not cross in the legal manner, by approaching immigration officials at official points of entry. The answer is also in Seifert’s backyard: the Matamoros Bridge, which links Brownsville, Texas to Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico.

[A member of the National Guard watches a portion of the Rio Grande river.]

Migrants’ Options Until This Summer: Cross the River or Wait Indefinitely

In previous years, when migrants seeking asylum crossed the Matamoros Bridge or other official points of entry to the US, a migrant could approach the customs station on the bridge, whereby a customs official would request documentation and the migrant could respond by asking for asylum. The official would then lead the migrant into the beginning of the process for seeking asylum. “Starting about May 15th of last year, you get to the top of the bridge, and right at the international boundary line, there are two or three officers. They ask to see your papers, and if, say, I’m coming to apply for asylum, they’ll say ‘we don’t have room today’ or ‘we’re not taking asylum seekers today.’ That’s against international and national law.”

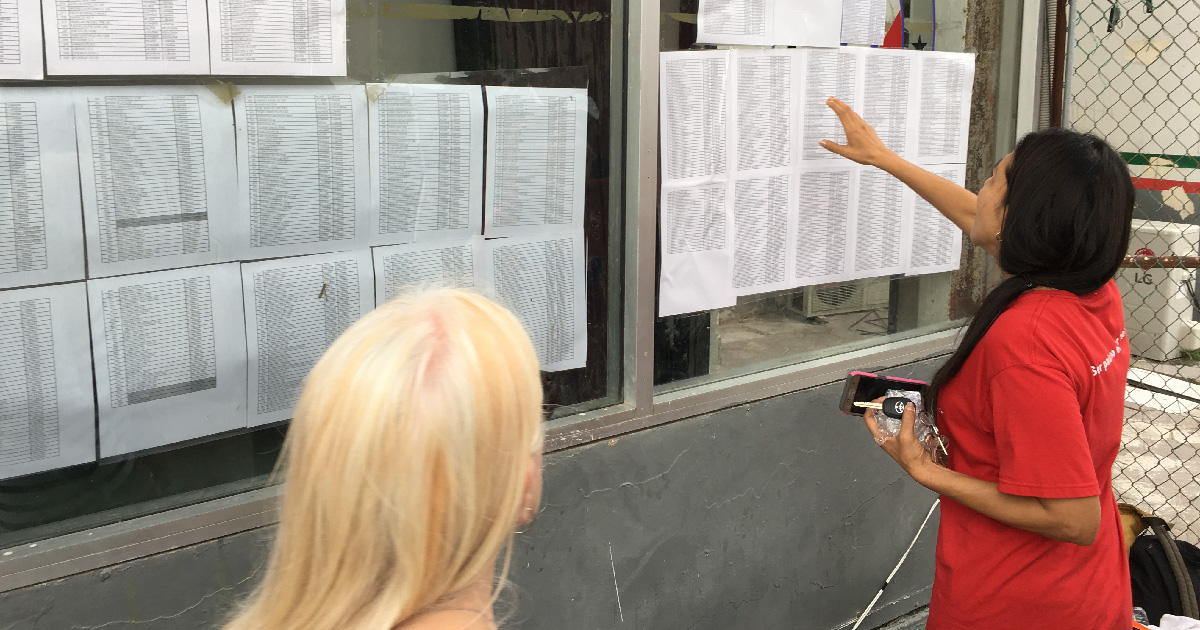

The slowdown at official points of entry resulted in hundreds of waiting asylum seekers on the Mexico side of the bridge. The customs office has lists of names taped in the window of the hundreds who are waiting for their name to be called. Often, one or two people are called per day. He estimates that 50 to 100 additional people arrive at the border daily. “People would have to live on the streets of Mexico for months,” Seifert said. And the streets are unsafe. Gangs and cartels target migrants because most have close relatives in the United States and are good candidates for exploitation, extortion, and kidnapping.

Nonprofits, many from his own community, stepped in to provide services. A group of retired teachers are running a pop-up school, reading stories and practicing the alphabet with young children under a tree. Other groups have put up porta-potties and brought hot lunches and dinners for the waiting migrants, but as the months have worn on and the numbers continued to grow, nonprofits have had to shift strategies. With supplies spread out over a greater number of people and for long stretches of time, “we’re down to PB&Js, they’re running out of food….It’s really a refugee camp without any organization,” he said. With the implementation of the MPP, service are even further stretched.

Migrant Centers: Overcrowding, Inhumane Conditions

Once migrants successfully begin the asylum process, they are brought to local detention centers. Overcrowded temporary facilities featuring chainlink fencing and a lack of provision of basic sanitary necessities like soap dominated the news cycle for months. What was not in the news, however, was a local’s understanding that the authorities were aware long ahead of time, and chose not to prepare.

“We knew what was coming down the road,” Seifert contends. During the 2014 “border surge,” federal officials saw the results of geopolitical forces in the Northern Triangle. “There were kids so packed in a room that they couldn’t sit down,” he said. Over the five intervening years, however, the federal government declined to revise its detention facility infrastructure to prepare for future surges. As a result, thousands of asylum seekers have slept on concrete floors in outdoor holding pens as federal authorities scrambled to open up additional centers; hundreds became ill while in overcrowded conditions; and at least six children have died in custody. “Detention is wrong, period,” he said. But the new changes, which are emptying detention centers, are not a humanitarian response to a humanitarian crisis.

Today on the Border: MPP

In recent weeks, yet another shift in policy has altered the landscape at the border. In August, the MPP came into effect, which requires asylum seekers to wait out their asylum cases in Mexico. Instead of releasing families from detention centers to the Respite Center or other local nonprofits, where they can then move to their new community and await their court date at a local court, they are left back on the Mexican side of the border, where they are once again subject to rampant violence and dangerous conditions, to await a court date at a tent court on the other side of the border. “They’re back in Mexico, with their kids, living on the street,” Seifert said. Back at the Respite Center, the number of asylum seekers dropped off from sometimes 800 people to just 43 in the first day after the change in policy. They may have to wait in Mexico for many months.

Meanwhile, news reports are indicating that poor organization and stretched resources -- and some conjecture purposeful intent -- prevent asylum seekers from making their way across the border to reach their court date in time, which results in automatic rejection of the asylum claim.

“They’re stuck,” Seifert said. This week, he says roughly 700 people are living on the streets on the other side of the Matamoros Bridge, which he believes is above the area’s capacity. “Half of them are six, seven, eight years old,” he added. “It’s a horrifically worse health situation” for the families to live on the streets. Every work day, roughly 200 more asylum seekers are dropped off on the Mexico side of the border as federal authorities empty US detention centers. “Where can they go? If you wanted to camp, there’s no place -- it’s maxed out. And it’s not a secure city,” so venturing further into the city and away from the vicinity of the border wall, which is policed by Mexican army officials, increases the risk of danger, he said.

The new policies that have emptied detention centers and virtually closed the border to asylum seekers are both being battled in court. “The MPP could be dismissed by the courts, any day. It’s just hard to know,” Seifert admitted. Similarly, the Supreme Court paved the way for the Safe 3rd Country rule to go into effect temporarily as its constitutionality is played out in the courts -- but it may, too, be struck down.

Migrants in Our Communities

Meanwhile, Seifert notes, thousands of newly arrived migrants have already made their way to communities around the country -- and their health needs must not be forgotten. “They are rudderless in many cases. Fortunately, they have family members here for many years, but often they are going to families that are already marginalized,” he said. These families may struggle to access care or send their children to local public schools, scared of jeopardizing their asylum cases by using public services. Most carry with them pre-, peri-, and post-migration trauma, for which local mental health services may need to be utilized.

Taking action, he notes, doesn’t just serve families who need help. It also helps him feel empowered. “In some ways, it’s easier to be in the middle of it all than to be reading about it and being angry about it. Here, [I can] just go to the bridge,” he said. Seifert encourages those who want to help asylum seekers at the border to look into their own communities and seek out groups that are supporting newly arrived asylum seeking families.

“Things change here all the time. It’s a volatile situation,” but he takes solace in knowing that clinicians have been serving migrants successfully, despite the challenge of mobility, for decades. “It’s quite an inspiration to see there has been a network of clinicians who have worked like this for many years,” he said.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.