- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in Electronic Health Records: Recommendations and next steps

National LGBT Health Education Center, Fenway Institute

[Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from two articles reprinted with permission from the Fenway Institute. Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Electronic Health Records is available at http://goo.gl/WJOvRc, and was made possible by grant number U30CS22742 from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care Promoting Health Care Access to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Farmworkers, a publication of the National LGBT Education Center, a program of the Fenway Institute, and Farmworker Justice, lists best practices for health centers in serving LGBT agricultural workers beyond data collection, like training all health center staff in general LGBT concepts, terminology, and health needs; including sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression in the health center’s non-discrimination policy; and using inclusive language for all patients. It is available at http://goo.gl/2HNC7z, and was supported by grant numbers U30CS22741 & U30CS22742 from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. The contents of both articles are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HRSA.]

Why Collect Data on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity?

There are no data regarding the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals in the agricultural worker community. However, outreach workers, clinicians, and researchers who provide health care and public health interventions to agricultural workers know from experience that LGBT people exist within the community, and that many face enormous challenges in accessing care, finding support, and feeling safe.1,2 LGBT “invisibility” within the agricultural worker community stems from strong cultural and religious taboos regarding sex in general, and sexual and gender minority identities specifically. It is common for LGBT persons to hide their identity in order to protect themselves from shaming, assault, and isolation from their families and communities.3 The stress caused by hiding one’s identity and dealing with stigma has been associated with higher rates of depression, suicide attempts, drug and alcohol abuse, and unsafe sexual behavior in LGBT people.4,5

Most clinicians do not discuss sexual orientation or gender identity (SO/GI) with patients routinely, and most health centers have not developed systems to collect structured SO/GI data. This invisibility masks disparities and impedes the provision of important health care services for all LGBT individuals, such as appropriate preventive screenings, assessments of risk for sexually transmitted infections and HIV, and effective intervention for behavioral health concerns that may be related to experiences of anti-LGBT stigma.5 Like all patients, LGBT people have behavioral as well as medical concerns, and want to discuss issues related to coming out, school, work, relationships, children, aging, and other issues that occur in different stages of life. An opportunity to share information about their sexual orientation and gender identity in a welcoming environment will facilitate important conversations with clinicians who are in a position to be extremely helpful.

Collecting SO/GI data in electronic health records (EHRs) is essential to providing high-quality, patient-centered care to LGBT individuals. SO/GI data collection has been recommended by both the Institute of Medicine and the Joint Commission as a way to learn about which populations are being served, and to measure quality of care provided to LGBT people.5-7 In addition, HRSA has proposed that SO/GI data be reported in the Uniform Data System for Calendar Year 2016. Gathering this data is therefore an important part of identifying and addressing LGBT health disparities in health centers and other health care organizations.

Recommended Questions

Sexual orientation and gender identity questions have been shown to be acceptable to health center patients from diverse backgrounds. In 2013, The Fenway Institute and the Center for American Progress conducted a study that asked 301 people in the waiting rooms of health centers in Chicago, Baltimore, Boston, and three rural South Carolina counties how they felt about answering questions about sexual orientation and gender identity. Most respondents were heterosexual and non-transgender; more than half were people of color; and seven percent were over age 65. Across all of these variables and regardless of geography, respondents overwhelmingly supported the collection of SO/GI data in health care encounters. Most respondents agreed that, “the question was easy for me to answer” and that, “I would answer this question on a registration form at this health center.” In addition, most LGBT respondents said that the questions accurately reflected their SO/GI.8

Based on this and other studies of SO/GI data collection, such as research conducted by the Center for Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California at San Francisco, we advise using the questions listed in Figure 1.9,10

Figure 1: Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Questions

Sexual orientation:

Do you think of yourself as:

⬜ Straight or heterosexual

⬜ Lesbian, gay or homosexual

⬜ Bisexual

⬜ Something else

⬜ Don’t know

Gender identity:

What is your current gender identity? (Check all that apply)

⬜ Male

⬜ Female

⬜ Female‐to‐Male (FTM)/Transgender Male/Trans Man

⬜ Male‐to‐Female (MTF)/Transgender Female/Trans Woman

⬜ Genderqueer, neither exclusively male nor female

⬜ Additional Gender Category/(or Other), please specify:____________

⬜ Decline to answer

What sex were you assigned at birth on your original birth certificate? (Check one)

⬜ Male

⬜ Female

⬜ Decline to Answer

Note that the gender identity question has two parts: one on current gender identity and one on sex assigned at birth. Together, these questions replace “Sex: Male or Female?” questions on patient information forms and in EHRs. Asking two questions gives a clearer, more clinically relevant representation of the transgender patient than asking just one question. For example, asking if someone is transgender will miss some transgender people who do not identify as such (e.g., a person who was born male, but whose gender identity is female, may check “female” rather than “transgender” on a form. The gender identity question also includes options for people who have a non-binary gender identity (i.e., people who do not identify as male or female).

In addition to asking about SO/GI, we strongly suggest asking patients to include their preferred name and their pronouns on registration forms (see Figure 2). This is important because many transgender patients have insurance records and identification documents that do not accurately reflect their current name and gender identity. In addition, some people who have a non-binary gender identity want to be called “they” rather than “he” or “she,” or use other gender neutral pronouns such as “ze” that are unfamiliar to many. Asking about preferred name and pronouns, and training all staff to use them consistently, can greatly facilitate patient-centered communication.

Figure 2: Preferred Name and Pronouns Questions

Preferred name:

Specify: ____________________

Pronouns:

⬜ He/Him

⬜ She/Her

⬜ They/Them

⬜ Other: ____________

Collecting the Data

There are several ways SO/GI data can be collected. For example, questions can be included on registration forms as part of the demographics section alongside information about race, sex, and date of birth; or they may be asked by providers during the patient visit. Patients may self-disclose to providers as a response to open-ended questions, such as, “Tell me about yourself.” Or, providers may ask as part of the social or sexual history, with a question such as, “Do you have any concerns or questions about your sexual orientation or sexual desires? Your gender identity?”

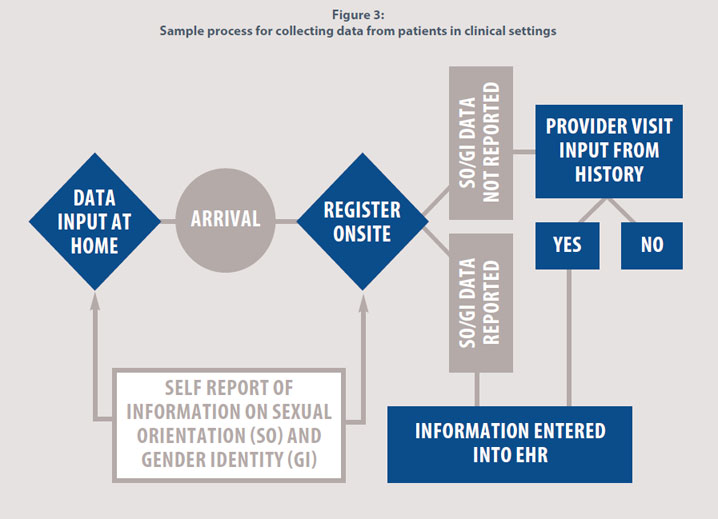

SO/GI information can be entered into the EHR by appropriate staff or directly by the patient through an online portal or mobile device. Whichever way the data is collected, SO/GI questions should be asked periodically, as sexual orientation and gender identity can change over time. Figure 3 illustrates a sample process of gathering SO/GI data in clinical settings.

Figure 3: Sample process for collecting data from patients in clinical settings

Training Staff

Health centers that collect SO/GI data need to ensure that all staff are first trained on effective communication with LGBT people. This training should include information on LGBT people and their health needs, as well as information on how to safeguard patient privacy and confidentiality. Training is available from the National LGBT Health Education Center at www.lgbthealtheducation.org.

Next Steps

There are various ways that SO/GI information can be incorporated into the EHR; there is no single system for accomplishing this. Health centers will need to work with their EHR vendors on how to structure questions as well as how to structure decision support (reminder systems) and coding. This also means it is important to educate insurers about standards of care for LGBT people so that reimbursement policies recognize the unique health needs of LGBT people.

The federal government is actively considering opportunities to support health care providers in asking SO/GI questions in clinical settings. As of spring 2015, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) has proposed health IT certification requirements calling for creating an optional module to collect SO/GI data. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ proposed Meaningful Use Stage 3 rule does not include collection of SO/GI data, although many are recommending its inclusion.6,7,11 To keep up to date on where these proposals stand, please refer to the Do Ask, Do Tell website at doaskdotell.org.

Conclusion

Given the documented disparities found in LGBT populations, it is critical for health centers to begin the standardized collection of SO/GI data in EHRs. Gathering this data will increase quality of care given to LGBT patients by allowing health centers to measure and track outcomes in these populations. Asking these questions also improves patient-centered care. Providers who are informed of their patients’ sexual orientation and gender identity – and are trained to care for LGBT patients– are better able to provide care that is relevant, specific, and compassionate. For further resources and information, see the Resources section below, and visit the National LGBT Health Education Center’s website at www.lgbthealtheducation.org.

References

- Somerville GG, Diaz S, Davis S, Coleman KD, Taveras S. Adapting the popular opinion leader intervention for Latino young migrant men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):137-48.

- Rhodes SD, Daniel J, Alonzo J, et al. A systematic community-based participatory approach to refining an evidence-based community-level intervention: the HOLA intervention for Latino men who have sex with men. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):607-16.

- Sue DW. Sexual orientation microagressions and heterosexism. In:Microagressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010

- Grant J, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011.

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. Available at www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13128.

- Institute of Medicine. Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in electronic health records: A workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. Available at www.iom.edu/Activities/SelectPops/LGBTData.aspx.

- The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission; 2011. Available at www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide.pdf.

- Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C, King D, Mayer K, Baker K, Makadon, H. Do ask, do tell: High levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107104. Available at http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0107104.

- Deutsch M, Green J, Keatley J, Mayer G, Hastings J, Hall A; the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: Recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(4):700-3.

- Deutsch M, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients—practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843-7.

- Public Comment on Stage 3 Meaningful Use proposed rule CMS-3310-P, published March 30, 2015. Submitted online: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3.