The health issues that face migrant and other mobile underserved populations are similar to those faced by the general population but are often magnified or compounded by their migratory lifestyle. Mobility results in poor continuity of care and simultaneously increases the need for care.1

Please click on each subtitle to learn more about each issue in migrant health.

Health care access Migrants struggle with similar challenges as other underserved populations regarding access to health care, but face the additional barriers of mobility, language, and cultural differences, lack of familiarity with local health care services, and limited eligibility to publicly and privately funded health care programs. While the uninsured rate for underserved Americans has dropped since the adoption of the Affordable Care Act, anecdotal evidence indicates that many migrant workers like farmworkers are unable to afford co-pays and deductibles.

Migrants are on the move -- but their health care might not follow. Their migratory lifestyles bring them out of their provider networks, reducing access further. Undocumented workers remain ineligible for coverage under the ACA. Fear of deportation and contact with governmental agencies makes access to health care even more complicated for undocumented migrants.

En-route health needs Migrants who are en route to a new location may encounter additional health risks such as heat or cold stress, dehydration, and exposure to disease, when crossing borders or traveling within a country. Migrants are more vulnerable while on the move, which may cause increased incidences of trafficking and exploitation; please see the Trafficking tab on our Women’s Health page.

At work Immigrant and migrant populations work in some of the riskiest industries in the country including agriculture, forestry, fishing and construction. Immigrants have higher rates of injury and fatality compared to workers in other sectors. In fact, foreign born workers are more likely to die on the job than those born in the US. Learn more on our Environmental and Occupational Health page.

Toxic exposures Farmworkers are exposed to pesticides in the fields. Farmworker families are also exposed. Paraoccupational exposure results from direct contact with farmworkers, such as parents or household members. Children and family members may also be exposed by pesticide applications and from pesticide drift. Toxic exposures don’t just happen to farmworkers. Migrant workers may be exposed to household and industrial cleaners, industrial manufacturing products, and other chemical exposures. Chemical exposure poses a huge range of health risks. Learn more and see some of MCN’s resources on pesticides on our Pesticides page.

Legal and regulatory concerns There is a long history of agricultural exclusions under various laws, resulting in insufficient on-the-job protections for farmworkers. MCN has long advocated for stronger Worker Protection Standards. Workers in all industries may not know their rights or may fear acting as a “whistleblower” when their rights are violated. MCN provides information for clinicians on our Worker’s Compensation page.

Housing and sanitation Migrant housing is associated with: pesticides exposures; unsafe drinking water; crowding; substandard and unsafe heating, cooking and electrical systems; inadequate sanitation; and dilapidated structures.2-6 Clinicians need to be aware of these additional health and well-being risks for migrant patients.

Food insecurity It is estimated that more than half of farmworker households are food insecure.7, 10-12 Farmworkers in migrant housing may face added food insecurity due to lack of access to transportation, food storage, and cooking facilities. It is estimated that more than half of farmworker households are food insecure. Several studies estimate that more than half of farmworker house-holds are food insecure.

Climate change Climate change disproportionately affects the poor more than other populations. Outdoor workers like migrant farmworkers are particularly vulnerable. Climate change is estimated to affect the health of outdoor workers through increased temperatures, more extreme weather, degraded air quality, and more vectorborne diseases.8 Migrants may have a higher risk of being exposed to these changes as a result of substandard housing (that may lack insulation and air conditioning) and outdoor work (resulting in increase in heat stress and other heat-related illnesses). They also may have fewer resources to help them adapt to the changes.

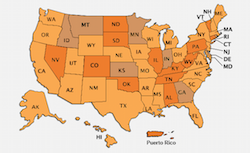

Clinicians serving migrants Throughout the United States, health centers are actively engaged to serve the migrant underserved populations in their communities. Health centers receiving Migrant Health Center Program funding in 2013 served almost 800,000 patients.9 (Federal funding is provided by the Bureau of Primary Health Care; learn more on our HRSA Health Program Clinical Requirements page.) Today, Migrant Clinicians Network serves over 10,000 constituents -- nurses, physicians, nurse practitioners, outreach workers, promotores de salud , administrators, pharmacists, dieticians, radiologists and many other types of clinicians dedicated to health justice for the mobile poor. You can search for a health center near you on our Health Center Map or learn more about a career in migrant health .

Explore Issues Explore Migrant Health Issues

All of the health care problems found in the general population are found in migrant groups. Some, however, occur more frequently. These include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and asthma. Tuberculosis deserves special mention in mobile populations. Migrant Clinicians Network provides overviews on the following issues in migrant health:

References Kugel C, Zuroweste E. The state of health care services for mobile poor populations: history, current status, and future challenges. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):421–429. Holden C, George L, Smith A. No refuge from the fields: Findings from a survey of farmworker housing conditions in the United States. Housing Assistance Council. 2001. Available at: http://www.ncfh.org/?plugin=ecomm&content=item&sku=5732 . Accessed on April 19, 2011. Government Accounting Office. Pesticides: improvements needed to ensure the safety of farmworkers and their children; 2000. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED439899&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED439899 . Accessed on April 15, 2011. Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Rao P, et al. Agricultural and residential pesticides in wipe samples from farmworker family residences in North Carolina and Virginia. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(3):382–387. Early J, Davis SW, Quandt SA, Rao P, Snively BM, Arcury TA. Housing characteristics of farmworker families in North Carolina. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(2):173–184. Gentry AL, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, Davis SW, Arcury TA. Housing quality among North Carolina farmworker families. J Agric Saf Health. 2007;13(3):323–337. Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Early J, Tapia J, Davis JD. Household food security among migrant and seasonal latino farmworkers in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:568–576.8 Schulte PA, Chun H. Climate change and occupational safety and health: establishing a preliminary framework. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2009;6(9):542-54. 2013 Health Center Data. HRSA Health Center Program. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?fd=mh . Accessed June 25, 2015. Hill BG, Moloney AG, Mize T, Himelick T, Guest JL. Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity in migrant farmworkers in Georgia. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:831–833. Quandt SA, Shoaf JI, Tapia J, Hernández-Pelletier M, Clark HM, Arcury TA. Experiences of Latino immigrant families in North Carolina help explain elevated levels of food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 2006;136:2638–2644. Kilanowski JF, Moore LC. Farmworker children at high risk for food insecurity, inadequate diet. J Ped Nurs. 2010;25:360–366.