- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- El Premio Kugel & Zuroweste a la Justicia en la Salud

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Tue, 02/09/2016 | by Claire Hutkins Seda

[Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing series which illustrates how young clinicians decided on the path to migrant health.]

[Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing series which illustrates how young clinicians decided on the path to migrant health.]

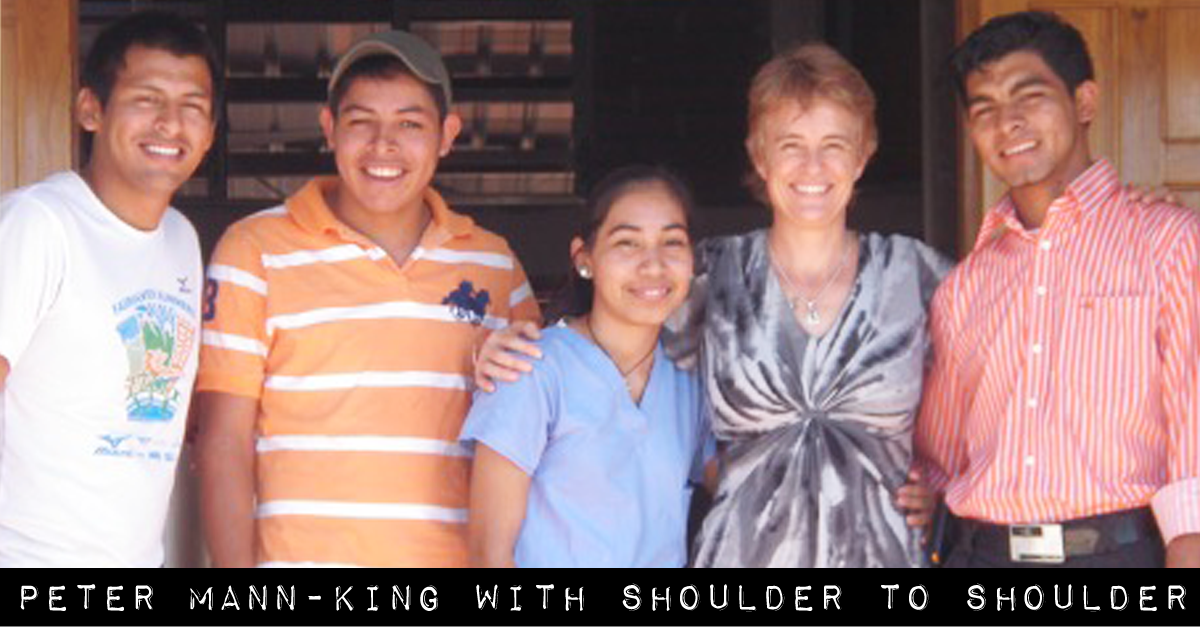

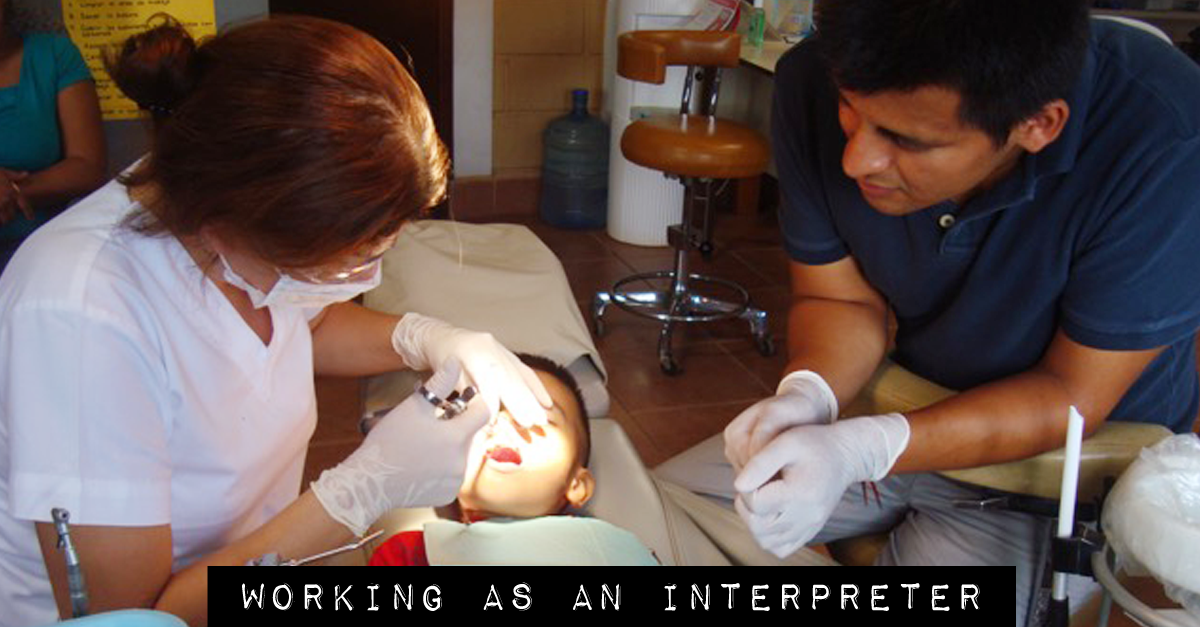

“In 2011, I moved down to la frontera,” between Honduras and El Salvador, recalled Peter Mann-King, to work with the non-profit Hombro a Hombro/Shoulder to Shoulder, where he worked in “a really remote rural community providing safety net services in conjunction with the government.” Mann-King had just finished his undergraduate degree in Latin American Studies at the University of Washington. Turning his theoretical studies into practical action with Hombro a Hombro, he collaborated with community members to improve access to basic needs like health care and education. “This was my first experience working with families ‘on the other side,’” outside of the US, he said, but his work was still closely linked to his home country. “The majority [of families] in that area had…. at least one family member per household that was living in the US or had made the journey at one point.”

During his yearlong position with Hombro a Hombro, Migrant Clinicians Network’s Ed Zuroweste, MD brought medical students from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine on a two-week multidisciplinary international health elective to the same region in Honduras, a trip he repeats about once a year. “I got to spend a lot of time with him and a few of the residents, and listened to his stories [about] the work he had done with migrant workers,” Mann-King recalled. “It was my first exposure to how influential health care can be for a more at-risk population.” He began to shift focus, including the health justice equation into his view of effective community development.

When he returned to the US, Mann-King stayed in touch with Dr. Zuroweste. Through MCN, he found an open position at Seamar Community Health Centers in Washington State at a clinic that serves about 40 percent Spanish speakers, a mix of second or third generation Mexican-Americans and some first generation immigrants from Central America and the northern reaches of South America. As a care coordinator, he provided case management and health education. “Instead of project development and working with the community as a whole to develop and implement a program, it was working with the newest migrants,” as individuals, providing yet another viewpoint on the day-to-day health needs of immigrants. Mann-King utilized MCN materials like the comic books depicting workers safety and health, and he attended MCN webinars to education himself more. “Seamar didn’t have the capacity to… create its own educational materials, so [I utilized] MCN’s toolkits for various topics to educate myself and I printed out a lot… for patients in the room, like those newly diagnosed with chronic disease, or when talking about occupational safety and health,” he said. “When I would think, ‘where do I start?’ I would always go to the MCN website first and see what was available.”

When he returned to the US, Mann-King stayed in touch with Dr. Zuroweste. Through MCN, he found an open position at Seamar Community Health Centers in Washington State at a clinic that serves about 40 percent Spanish speakers, a mix of second or third generation Mexican-Americans and some first generation immigrants from Central America and the northern reaches of South America. As a care coordinator, he provided case management and health education. “Instead of project development and working with the community as a whole to develop and implement a program, it was working with the newest migrants,” as individuals, providing yet another viewpoint on the day-to-day health needs of immigrants. Mann-King utilized MCN materials like the comic books depicting workers safety and health, and he attended MCN webinars to education himself more. “Seamar didn’t have the capacity to… create its own educational materials, so [I utilized] MCN’s toolkits for various topics to educate myself and I printed out a lot… for patients in the room, like those newly diagnosed with chronic disease, or when talking about occupational safety and health,” he said. “When I would think, ‘where do I start?’ I would always go to the MCN website first and see what was available.”

At Seamar, Mann-King got to see his Hombro a Hombro community on the US side. “I worked with a Honduran family during their reunification… The mother hadn’t seen her daughter for almost 15 years,” Mann-King remembered. The mother, who had a new life in the US, with other US-born children, brought the daughter to the clinic for assistance with social support issues -- to assist the family through the reunification process. “It put together a lot of the pieces. It showed me that migration -- the story of immigration as a whole -- is very complex.” He followed the family for two years and was rewarded by watching their progress, he said.

After two years at Seamar, Mann-King developed a vision of working for immigrants in the US from a “systematic policy level.” He is now in his second year at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Public Policy & Management. He will complete his Master’s degree in Health Care Policy & Management at the end of the current semester. He has become closely involved with his adopted community there in Pittsburgh, working for the local Federally Qualified Health Center, Squirrel Hill Health Center -- but the picture is once again quite varied from his previous work, exposing him to a new swath of immigrants, with their own health needs and distinct cultures. The clinic is housed in a predominantly Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, and his work creating a registry for TB patients for the center has him focused largely on Butanese, Nepali, and other patients from Southeast Asia.

After two years at Seamar, Mann-King developed a vision of working for immigrants in the US from a “systematic policy level.” He is now in his second year at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Public Policy & Management. He will complete his Master’s degree in Health Care Policy & Management at the end of the current semester. He has become closely involved with his adopted community there in Pittsburgh, working for the local Federally Qualified Health Center, Squirrel Hill Health Center -- but the picture is once again quite varied from his previous work, exposing him to a new swath of immigrants, with their own health needs and distinct cultures. The clinic is housed in a predominantly Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, and his work creating a registry for TB patients for the center has him focused largely on Butanese, Nepali, and other patients from Southeast Asia.

As for the long term, Mann-King sees himself working on the bigger picture, to “serve individual populations differently and effectively in a culturally sensitive way,” through work at the policy level, through program development and management, and through innovative uses of data and analysis. We at MCN can’t wait to see what he does next.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.