- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- El Premio Kugel & Zuroweste a la Justicia en la Salud

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Eyes Wide Open, and Hopeful: On Receiving the Second COVID-19 Vaccine Injection, From a Hospitalist on the Frontlines

Wed, 01/20/2021 | by Laszlo Madaras

By: Laszlo Madaras, MD, MPH

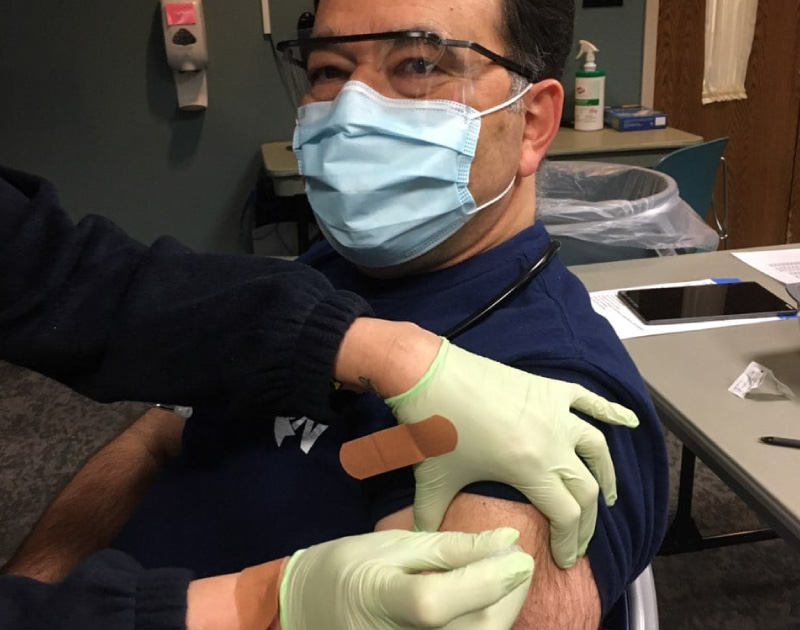

[Editor’s Note: Hundreds, if not thousands, of frontline clinicians in our clinical network have received their initial doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. Many took selfies as the shot was administered, with smiles of hope and jubilation. Here, Laszlo Madaras, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Officer for Migrant Clinicians Network and a doctor who has assisted hundreds of patients suffering and dying from COVID-19 at the ICU of a rural hospital in Pennsylvania, reflects on the vaccine he himself has taken. Get more information on the vaccine from Dr. Madaras’s recent piece for clinicians on Healio: “Q&A: What PCPs Need to Know about COVID-19 Vaccines.”]

I write this after having received the first Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine and anticipating the second injection of the same in a few hours. Some of my friends say I am lucky to be one of the first to get the vaccine, others feel I am foolish in volunteering as a guinea pig, and others consider me brave for the same reason. There are many different views on this rapidly produced vaccine as reflected in all of those opinions. (Also, I am particularly fond of "guinea pigs" since I was a kid in Maine watching the first American walk on the moon.)

The vaccine has become available much faster than any before. Part of the reason had to do with molecular biology and genetic research rapidly advancing in the last decades. We know so much more than we did when this author majored in biochemistry in 1983, or even after completing medical studies a decade later. The work on mRNA and mRNA vaccine strategies has been ongoing and NOT just begun with the arrival of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Also, with much of the world focused on COVID-19, there was much red tape removed to allow the vaccine(s) to advance to trial quickly. However, the critics of the rapid initiation of the vaccination distribution should be heard, not because of its fast arrival, but because of two reasonable concerns:

- Not enough time has passed in phase III of human trials to understand the complete risk versus benefits of the vaccine over many years – and this is a risk we must take, given the novelty of the virus. The test subjects were followed for only a few months. We have no long-term data on a virus we just learned about in the last 12 months. There are unknowns – and by getting this vaccine now, I accept that I am still involved in an ongoing vaccine trial.

- There have not been enough people vaccinated to see small risks that may be, for example, only one in 10 million, until we vaccinate about 10 million and establish whether that small risk that now shows up is nevertheless lethal enough to weigh risk and benefit toward modification of the vaccine.

Those who say "no vaccine is needed since most people recover and this is just a bad flu" should spend time with me in the halls of our hospital ICU and COVID medical floor. You are wrong. I have spent every year since 1993 treating hospitalized patients including each and every influenza season during those years. This is much worse than any influenza I have ever encountered.

In the first decades after World War II in Europe, newborns were vaccinated against tuberculosis, specifically TB meningitis, which was a significant killer of the young in the last century. Now very few doctors in Europe and the US treat this rare disease except in other parts of the world (where the BCG vaccine is still frequently given). Unfortunately, BCG does not protect for an entire lifetime, and TB later in life still needs treatment with oral medication. Nevertheless, that once-in-a-lifetime vaccine did buy newborns like me a chance at a healthier childhood. We were also protected with a pink liquid put onto a sugar cube – the oral polio vaccine – which meant our fellow grade schoolers no longer needed iron lung machines and didn’t encounter closed summer swimming pools due to polio outbreaks like the generation before us. Our summers climbing and building tree houses - sometimes with rusty secondhand nails - were safer thanks to the tetanus vaccine with lifetime boosters every 10 years. I know stories of my grandfathers' friends and one sibling who died of tetanus in Europe between the world wars before DTaP vaccinations were common. The physicians of my generation have not had to treat much tetanus in the US (I have had one case in the US and two while working in central Africa) thanks to a strong childhood vaccination program. And this is true for so many successful vaccines that, unlike parents in more resource-poor countries, young parents in the US no longer witness these diseases and therefore some no longer recognize the benefits of vaccines, only the risks.

I believe the COVID-19 vaccine will take its place in the pantheon of other vaccines, and eventually the vaccination duration and frequency will be determined – once in lifetime (like BCG), once every 10 years (like tetanus), once a season (like the fluvax) or some other frequency.

I take this second vaccine with eyes wide open. With my hospitalist group, I have worked with now several hundred COVID-19 patients and witnessed too many deaths to ever want to see another. But I know I will see more deaths in 2021 and I need help. In this battle, I consider the vaccine as part of my body armor and camo against a very lethal adversary. I know we do not have a full understanding of the vaccine, but volunteering to be one of the first is also a way to show leadership and confidence in ongoing science. So to all my friends who consider me lucky, foolish or brave, let's just say I am hopeful, and that this action is a response to JFK's call: "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country."

Postscript: I received the second injection and am doing well. A sore arm and some general body aches like the first day after a good marathon run, and feeling even better after the second day.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.