- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- El Premio Kugel & Zuroweste a la Justicia en la Salud

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Thu, 01/20/2022 | by Kaethe Weingarten

[Editor’s Note: In this month’s Witness to Witness blog post, Kaethe Weingarten, PhD, Director of Witness to Witness, offers us perspective on uncertainty. Visit Witness to Witness page here. You can also sign up for MCN’s four-part online seminar series entitled, “Managing Stress in Challenging Times,” a professional development and peer support program for health care workers on our Upcoming Seminars page.]

For most of us, this has been a year of uncertainty. Whether in our roles as a family member, friend, or clinician, we can take steps to be helpful to others who are living through the uncertainty of waiting, when people expect a resolution to a problem but have to manage the time before the resolution presents itself.

Kinds of Waiting

All uncertainties are not the same, so waiting isn’t either. There are different lengths of waits, so the beginning, middle and end of the wait may have different qualities. So too the outcomes of different situations have different stakes, so waiting is likely to feel different. Waiting to see if a vaccination shot will hurt is a different kind of wait than not knowing if your hospitalized loved one will require intubation.

At the same time, how people feel about different kinds of uncertainties is personal; what might be insignificant to you, relatively speaking, may nonetheless be highly significant to someone else for reasons they may or may not be able to articulate.

With that in mind, we might be well advised to assume that all waits have their challenges.

Coping Styles

People vary in how they handle the uncertainty inherent in waiting. Research suggests that there are two overarching coping styles, characterized as dispositional or strategic optimism and defensive pessimism, although not everyone fits neatly into one of these two coping style preferences. Julie Norem suggests that a strategic optimist generally expects things will be all right, doesn’t worry too much in advance and assumes that most outcomes can be handled.1 A defensive pessimist anticipates a worst-case scenario and mentally prepares for it.2 Either strategy can work well or ill, depending on the specifics of the situation.

Strategies to Reduce Anxiety

Kate Sweeney has been studying uncertainty for most of her career. She writes: “During difficult waiting periods people can mitigate anxiety, reduce disruptive rumination, and minimize later harm by (1) distracting themselves from their uncertainty, (2) managing their expectations, (3) looking for the silver lining in all outcomes, (4) keeping perspective regarding the news, and (5) planning ahead for the objective and psychological consequences of bad news.”3

Supporting Someone who is Waiting

When any of us waits for results, we will either wait alone or with others. Whoever else knows about the wait, will, of course, have their own coping style preferences too. These may harmonize or conflict with ours.

For the most part, it won’t ever be helpful to tell someone who is waiting, “Don’t be anxious.” This is surely no better than saying, “Don’t think of a polar bear.”

Nor is it helpful to inform people that “hoping for the best and planning for the worst” –advice with its origins in the 18th century -- is the best approach to waiting. The two terms of the adage refer to two coping strategies and they are generally used by different people. Instead we can say, “There are lots of different ways that people cope with waiting. Do you have a sense of what style works best for you?”

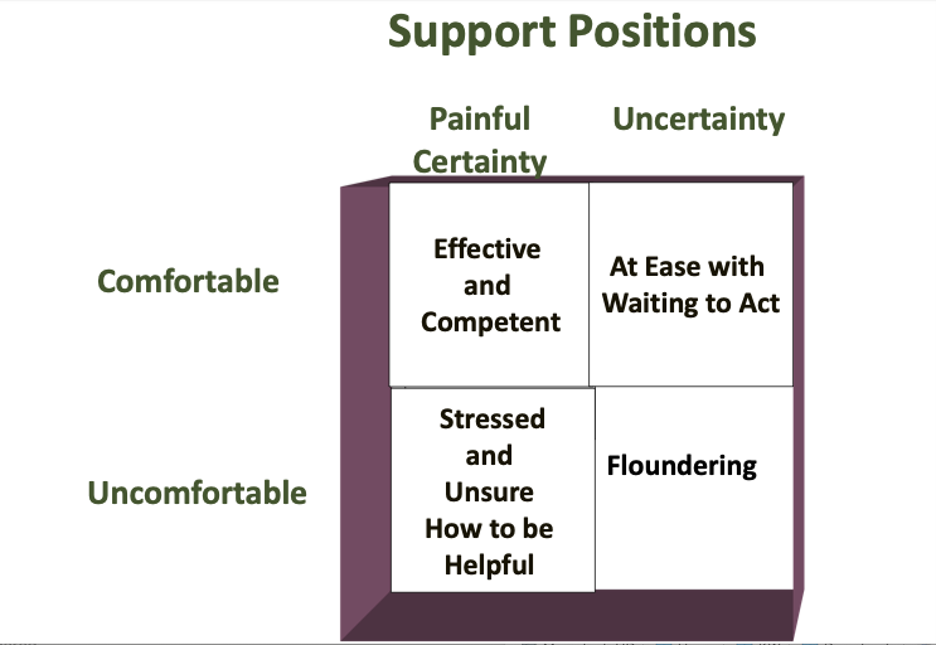

Whether we want to be or not, if we accompany someone through a period of uncertainty, we become their witness. Our way of managing our own witnessing position with regard to uncertainty will impact others. As suggested in Figure 1, we can be comfortable or uncomfortable with uncertainty and, for that matter, painful certainties, which are sometimes the outcome of a wait. If we volunteer to be present for someone coping with uncertainty, it’s a good idea to be comfortable ourselves. Otherwise, we may add to, not diminish, the stress of waiting, an outcome nobody wants.

Hopefully, most waits will resolve well. When they don’t, if we have been there for another person, that is the kind of comfort that is appreciated and long remembered.

Figure 1.

Norem, J. K. (2001). Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 77–100). American Psychological Association.

The difference between dispositional and defensive pessimism is that defensive pessimism involves preparing for any situation, whereas dispositional pessimism relates to believing that everything will turn out badly.

Sweeney , K. (2012). Waiting Well: Tips for Navigating Painful Uncertainty. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 6/3: 258–269.

1 Norem, J. K. (2001). Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 77–100). American Psychological Association.

2 The difference between dispositional and defensive pessimism is that defensive pessimism involves preparing for any situation, whereas dispositional pessimism relates to believing that everything will turn out badly.

3 Sweeney , K. (2012). Waiting Well: Tips for Navigating Painful Uncertainty. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 6/3: 258–269.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.