- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- El Premio Kugel & Zuroweste a la Justicia en la Salud

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Wed, 11/30/2016 | by Claire Hutkins Seda

On Monday, Texas health authorities reported its first case of locally transmitted Zika. Just 10 days earlier, the World Health Organization (WHO) topped the public health news feeds with its declaration that Zika is no longer a global health emergency. What does the change in designation mean for populations at risk of contracting Zika, in the US where Zika continues to spread, in Puerto Rico where it’s reached epidemic proportions, and elsewhere? What does it mean for clinicians serving populations in the US who are the most at risk of contracting the virus?

The WHO’s global health emergency designation in February of this year aimed to answer one central question: was the terrifying increase of microcephaly among infants in parts of Brazil related to the Zika virus? Months later, the link between an expecting mother’s Zika infection and the development of the severe birth defect in her infant has been established through multiple studies. Meanwhile, thousands of people have contracted the virus as it has spread throughout the Americas. The latest case in Texas comes on top of the more than 200 confirmed Zika cases contracted locally in Florida.

“The change in the WHO’s position seeks to underscore the need to develop and identify consistent and ongoing sources of funding to address Zika,” explained Del Garcia, MCN’s Director of International Projects, Research, and Development. In other words, as the central question that drove the WHO to declare Zika a health emergency has been answered, health authorities must pivot away from the initial (and at times frantic) research on Zika and its link to microcephaly, and instead recognize and prepare for Zika for the long run as “a significant enduring public health challenge requiring intense action,” according to the WHO statement on the change in designation.

Dr. Ed Zuroweste, MCN’s Chief Medical Officer, puts the designation into perspective. “Tuberculosis is not a global health emergency, despite the fact that TB will be responsible for another probable 1 to 1.5 million deaths in the world again in 2016, as it was in 2015.” While the designation indicates a shift in how we talk about Zika, it does not lessen its urgency.

But the revision in the WHO’s Zika terminology may have unwanted effects. “We are fearful that, based on this change of status, people will stop being vigilant when what is required is an absolute incorporation of the risk reduction practices because Zika -- along with dengue and chikungunya and other mosquito-borne illnesses -- remains a very serious health concern,” Garcia said.

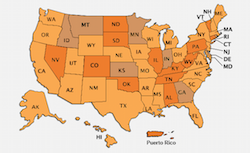

Many of the migrant patients we serve travel between areas of outbreak and the US; in Puerto Rico, patients are vulnerable to mosquito bites from infected mosquitoes even as they make their way to the clinic. Despite the change in WHO designation, clinicians need to continue to be vigilant:

Take a complete history to identify those who may be at risk for the Zika virus. Women of childbearing age should be asked about their plans for conception.

Know the signs and symptoms of Zika, dengue, and Chikungunya -- see our Zika page for more on each.

Provide education to patients at risk. Give information about sexual transmission, the link to microcephaly during pregnancy, tactics to remove mosquito breeding areas in the community and around the house, and ways to prevent mosquito bites.

Migrant patients suspected of infection may be enrolled in Health Network, to assure continuous monitoring or to enable the receipt of test results at the patient’s next location.

Learn more and keep up to date through the CDC’s Zika page and through MCN’s Zika Virus, Other Mosquito-Borne Illnesses, and Migrant Patients.

- Take a complete history to identify those who may be at risk for the Zika virus. Women of childbearing age should be asked about their plans for conception.

- Know the signs and symptoms of Zika, dengue, and Chikungunya -- see our Zika page for more on each.

- Provide education to patients at risk. Give information about sexual transmission, the link to microcephaly during pregnancy, tactics to remove mosquito breeding areas in the community and around the house, and ways to prevent mosquito bites.

- Migrant patients suspected of infection may be enrolled in Health Network, to assure continuous monitoring or to enable the receipt of test results at the patient’s next location.

- Learn more and keep up to date through the CDC’s Zika page and through MCN’s Zika Virus, Other Mosquito-Borne Illnesses, and Migrant Patients.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Send it to us via email, on Facebook, or on Twitter.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.