- Who We Are

- Clinician Employment

- Publications

- Witness to Witness (W2W)

- El Premio Kugel & Zuroweste a la Justicia en la Salud

- Your Voice Matters: Photovoice Project

Wed, 06/06/2018 | by Claire Hutkins Seda

[Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of articles on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Read our first installment, written by Dr. Eva Galvez, here. Part three will explore the health consequences of recent policies around immigrant family separation at the border.]

Divorce, violence in the community, a family member incarcerated or deported, physical or sexual abuse, a lengthy and dangerous migration. For many people across the US, adverse experiences like these define childhood and adolescence, dropping children into “toxic stress,” a type of stress response that is excessive and prolonged. Toxic stress can detonate lifelong health issues and derail healthy development. Well-known is the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and mental health concerns like depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Less acknowledged is the lasting impact on physical health.

“These data have been out for quite some time, but it’s taken a few years for people to uptake these findings,” explained Javier Rosado, PhD, Director of Clinical Research at Florida State University’s Center for Child Stress & Health. He’s talking about the seminal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Kaiser Permanente ACE Study from the mid-1990s, which linked current health status with childhood experiences among the 17,000 patients studied. As the number of ACEs went up, so did the risk for a huge range of health concerns, from alcohol abuse, to ischemic heart disease, to early initiation of smoking, to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The findings created a wave within the public health community, but, over 20 years later, many health centers still grapple with how to implement programs to offset the harm of ACEs. The trouble begins -- but doesn’t end -- with screening. “The American Academy of Pediatrics tell us to screen children for ACEs so we can intervene early -- but the difficulty with this is that, although there’s clear evidence for the need to screen, there hasn’t been much research on how to do that,” Dr. Rosado noted.

Some health centers hesitate to initiate screening for ACEs because of lack of a workflow to assure follow-up after screening. “A lot of clinicians are scared about opening up this can of worms,” Dr. Rosado empathized. “We ask questions about mental health, substance abuse -- but then what are we going to do about it?”

Dr. Rosado’s team at the Center for Child Stress & Health has developed a three-part approach to assist health centers to incorporate the findings of the initial and subsequent studies on ACEs through education and new resources, starting with extensive webinar series on toxic stress, facilitated by Migrant Clinicians Network.

Webinar Series:

“We’ve developed a web-based training curriculum for promotores on toxic stress to educate families and get the word out,” Dr. Rosado explained. The five-year project, supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), will feature two webinars a year for each program year focused exclusively on toxic stress and ACEs. While promotores often have a specific focus or expertise -- for example, on nutrition or diabetes -- few have expertise on mental health. Part of the goal of the series is to improve participants’ competency and comfort level related to talking to community members about mental health.

“Preparing community health workers, who are often the bridge between the community and the health care system, to broach mental health as an important element of overall health, helps to normalize the conversation,” explained Deliana Garcia, MA, Director of International Projects and Emerging Issues.

Screening Tool:

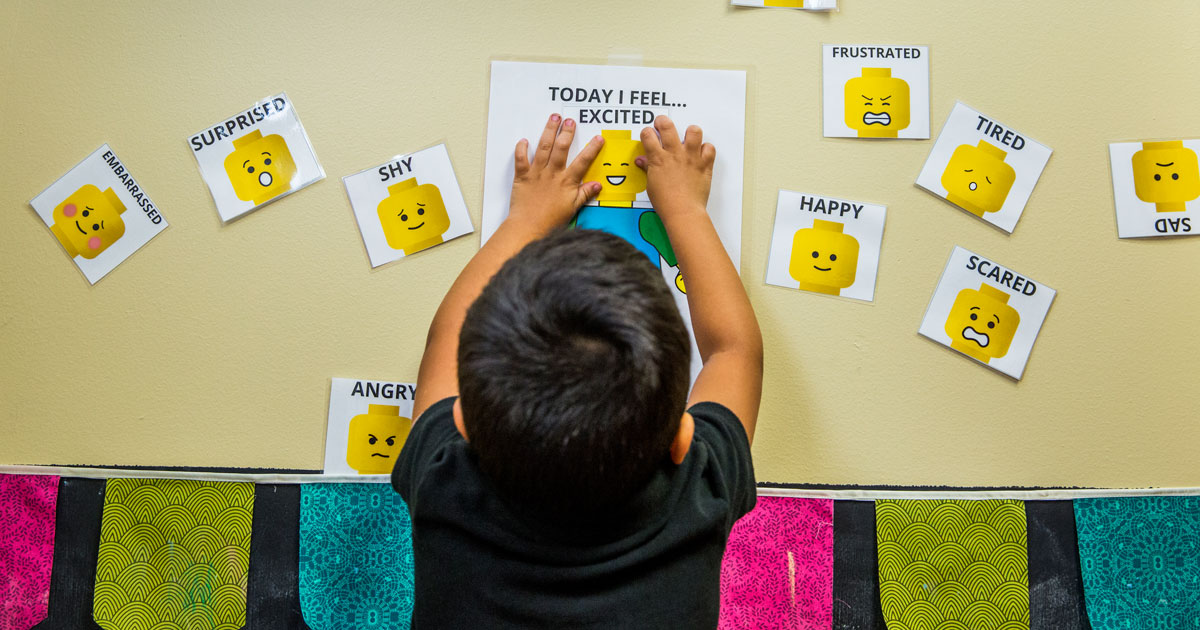

The second component of the Center for Child Stress & Health’s approach is the development of a screening tool. Designed for use in pediatric practices, the low- to no-literacy screening app is presented through an electronic kiosk, an interactive program that the patient uses on a touch-screen tablet. Responses are coded by color and shapes.

Dr. Rosado’s team has already trialled their first version with patients at their pediatric clinic in Immokalee. Over the course of 12 months, the clinic screened 1,500 pediatric patients during well-child visits. The kiosk is now a part of the workflow: every child above the age of six that comes to the pediatric department from the mobile agricultural worker community is screened. The project is scheduled to lower the minimum age of screening to age three. Mothers are also being screened for their own ACEs, as a mother with more ACEs is more likely to have a child experience ACEs. And, the Child Stress and Health project is growing: they’re currently implementing the program at a school-based clinic nearby.

Despite early successes, the trial uncovered some elements that could use adjustment. “We took for granted that people would know how to use a tablet -- for example, to touch the tablet to turn it on. The second version has face recognition, so it will turn on by itself,” Dr. Rosado noted. The redesign incorporates “little things like that [to] make the app as independent as possible, because we know that health centers don’t have extra staff waiting around to help people.”

Once responses are received, the app generates a report that can be linked directly to the medical record for a provider to review. The second version will automatically print patient education materials in the patient’s preferred language based on his or her responses. Dr. Rosado believes the app has great promise for other clinics serving migrant farmworker populations as it’s tailored for that population, and is available in English, Spanish, and Creole.

Workflow adjustments:

The third aspect of the approach aims to assure that clinicians can utilize new knowledge from the trainings and act on the findings of the screenings. Dr. Rosado questions, “Once you have a positive screening, who responds to it? What options do you have? What resources do you need?” The Center for Child Stress & Health’s website already hosts a number of resources for parents on which clinicians can lean, but they plan to take it a step further by uploading a suite of interventions in a mobile-friendly format.

Early discoveries:

Preliminary analysis of the data from the first 12 months of the program’s operation in Immokalee painted a stark picture of a community’s needs. “The number one ACE event is incarceration or separation -- but upon follow-up, [we found that] it wasn’t incarceration but issues related to deportation or detainment related to immigration status,” Dr. Rosado explained. “Our response has been to develop a set of resources to help parents talk to their children through that form of stress.” They’ve also launched community workshops to talk about this “unfortunately very real fear” of deportation and how to have appropriate conversations with children about it. Dr. Rosado, a psychologist, notes that high anxiety around immigration concerns isn’t limited to those who lack authorization to live in the US. Dr. Rosado cited his own pediatric patients exhibiting high levels of anxiety despite their own and their parents’ citizenship. “They may still say, ‘it affects my best friends’ or ‘his parents had to leave.’ It impacts the whole community.”

Another ACE that caught Dr. Rosado’s attention was emotional neglect among adolescents. “We have found that adolescents are endorsing items related to feeling unloved or unsupported by their family,” he said. “Because of the nature of the lifestyle and work demands on farmworkers -- migrant farmworkers in particular -- it becomes really difficult to connect with your child emotionally, because of a lack of time and differences in culture. But we see kids who are yearning to be emotionally connected.” He noted that parents desire the connection as well, but their time and thoughts are occupied with providing basic needs like food and shelter. “It’s been a good opportunity to tell parents that [their teens] want to connect with them despite their behaviors,” and one-on-one time, even if limited, can help satisfy the need for that emotional connection.

On average, by the age of nine, almost 30 percent of the screened pediatric patients have experienced two ACEs. “That’s of concern, and signifies the need for more work in this area, both screening and prevention,” Dr. Rosado said.

Resources:

Information on toxic stress, screening measures, workflow recommendations, and numerous resources are viewable at the Center for Child Stress & Health website:

https://med.fsu.edu/?page=childstress.home

The Center for Child Stress & Health’s resource website for patients (both children and adults) is at http://www.fsustress.org/

Information on toxic stress, screening measures, workflow recommendations, and numerous resources are viewable at the Center for Child Stress & Health website:

https://med.fsu.edu/?page=childstress.home

The Center for Child Stress & Health’s resource website for patients (both children and adults) is at http://www.fsustress.org/

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.